- Share via

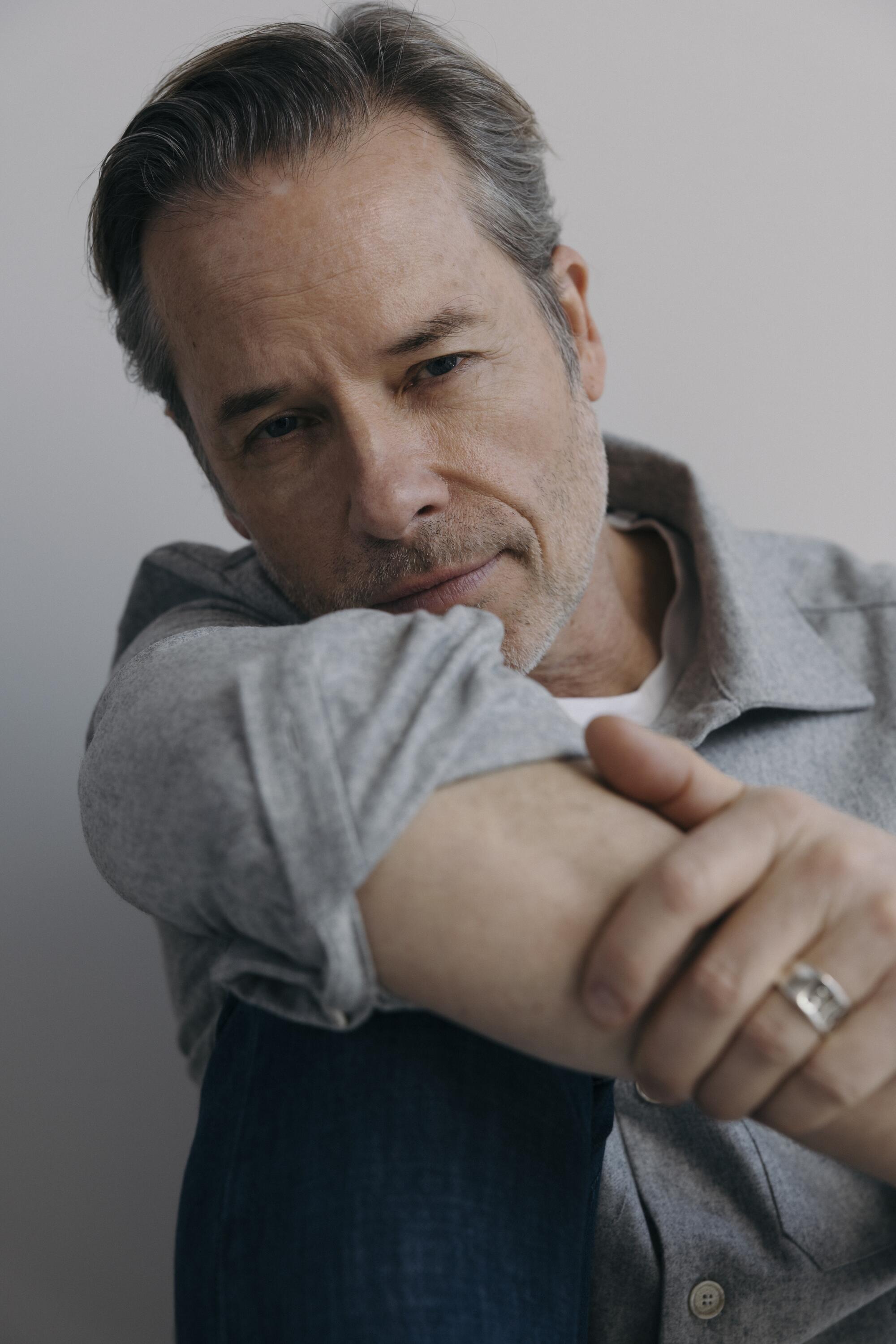

Every time Brady Corbet makes a movie, he’s thinking, “This could be the last one.” He doesn’t want it to be the last one, but when you’re filming, say, a 3½-hour drama about the artistic struggles of a fictional architect, you never know.

“There’s a high likelihood,” Corbet says, smiling.

“The Brutalist,” nominated for 10 Oscars including best picture, directing, the original screenplay Corbet wrote with his partner, Mona Fastvold, and for actors Adrien Brody, Felicity Jones and Guy Pearce, will not be Corbet’s last movie. The film has become an event, a must-see for movie lovers. It’s both epic and intimate, a portrait of an immigrant architect, László Tóth, that examines the relationship between patron (Pearce) and artist (Brody), and considers the purpose and lasting value of art.

Much remains unspoken in “The Brutalist,” allowing us to use our imaginations to fill in the gaps.

“That’s what makes the film so grown-up,” Jones says. “The audience becomes active participants.”

But that doesn’t mean we’re not interested in exploring the movie’s themes and mysteries. Corbet, Brody, Jones and Pearce, calling in from various corners of the world, were more than happy to provide some answers.

Why does Van Buren, the wealthy industrialist who becomes László’s benefactor, use the line, “I found our conversation persuasive and intellectually stimulating” — twice — in their first meetings?

Pearce: Let’s call it the ridiculousness of the man. I know it gets a bigger laugh the second time, but the first time he says it in the cafe, there was nothing intellectually stimulating about that conversation. Adrien was just sitting there, like a teenager being told off in a principal’s office.

The veteran actor, known for “Memento,” “L.A. Confidential” and HBO’s “Mildred Pierce,” has been earning praise for his complex portrayal of an enigmatic industrialist.

Might Van Buren have feelings for László that go beyond the intellect?

Brody: There are a lot of emotions at stake. I don’t disagree, but it’s more complex than that.

Pearce: There are indicators of his attraction, some even within the dynamic of the three of them [László, his wife, Erzsébet, played by Jones, and Van Buren]. It is a bit of a love triangle, isn’t it? When she finally turns up, I’m going, “This person has come to take my man.”

Is that why Van Buren was so keen on getting her a job in New York almost immediately? “You’ll only be gone ... five days a week.”

Pearce: Yes! “Keep away from my find!”

Jones: Erzsébet’s experiences with trauma have made her so aware of how terrible human beings can be. From the moment she meets Van Buren, she knows who he is and that he’s a problem.

Brody: László possesses qualities that Van Buren doesn’t. With all his power and ability, he doesn’t have the same creative spirit. There’s something when you encounter someone who is so uniquely creative. You appreciate it. It’s something to marvel at.

Pearce: When I press my face to the marble [at the quarry, when László takes Van Buren to look at marble for the center he’s building], Brady was quite specific about wanting me to look at [László]. That in itself is one of the little tells about my attraction to him — on all sorts of levels. There’s something deliberately coy and seductive that I bring him into my experience I’m having with this marble.

Brody: It’s a love- and hate-filled dynamic. There’s antagonistic superiority and disdain amid love and appreciation and adoration for his creative spirit. There’s a very convoluted thing going on.

The eight-minute conversation at the Christmas party between László and Van Buren, the one that’s been called the “skeleton key” to understanding the movie, has Van Buren telling a long, cruel story about stiffing his grandparents, ending it by saying, “That is how much I love my mother.”

Pearce: That’s such a spiderweb, isn’t it?

Just how much does Van Buren love his mother?

Pearce: Someone said to me the other day, “We get to see what a mummy’s boy he was.”

Corbet: I thought of the mother as Rebecca at Manderley, this specter that haunts the house. It seems to be a rather unhealthy obsession. And it feeds the concept for the whole project. He has this scene where he describes to László how he knows how to read the tea leaves and the fact that the two of them came together on the eve of his mother’s death, which is what leads him to do something that’s equally mad.

Pearce: There’s this performative façade of strength to Van Buren, but on some level, he feels powerless. And he feels that the only way to actually get over that is to present himself as powerful. And in that conversation with László, you see he recognizes László’s artistry, but that’s tangled up with his own insecurities about not possessing those qualities himself.

Corbet: He’s not satisfied just to own the artist’s work. He wants to possess the artist as well.

Which we see, quite literally, later in the movie when Van Buren rapes László. Some critics have found the scene rather abrupt and tonally jarring. Why did it seem necessary?

Pearce: The main question I had for Brady was the justification and the understanding of what happens.

Corbet: For me, you should see it coming from miles away. After two hours and 45 minutes, there’s a lot of threads there.

Brody: I think it’s intended to be a big surprise to the audience. But when I read it, I did see it coming.

Jones: That scene is so pivotal. It’s so necessary. What’s so striking about the film is that it is full of hope, but the hope comes from trauma. You can’t have one without the other.

Pearce: I think Brady brilliantly keeps open about how much this has happened before, whether [Van Buren] is a repressed homosexual. But what jumped out at me is when we see Joe Alwyn [playing Van Buren’s son, Harry] running up and down those stairs [after Erzsébet confronts him about the rape], going, “Father! Father!” I looked at that and went, “Ah. Wow. I reckon I have abused him.”

Corbet: The way Joe Alwyn responds to Felicity’s accusation, especially after we’ve seen him take Zsófia [László’s orphaned teenage niece] into the woods. You see this cycle of violence in the family.

Brody: It’s not as simple as a metaphor for being literally screwed over by your benefactor. It pertains to a deeper hatred. We shot it in multiple ways, in a much more graphic way as well. It speaks to a kind of oppressive brutality of dominance, what makes individuals so cruel and insensitive and behave so despicably at times.

Corbet: The film was made in the style of a 1950s melodrama. The way that I was thinking about it was: What would Nicholas Ray do if he could get away with it today in 2025? It’s not a neorealist picture. I was thinking about Powell and Pressburger. There’s a largess and there’s a directness in the films, allegory and visual allegory. There’s interplay between graceful moments and more direct, operatic moments. That’s what gives the film, and all my films, a very specific, very jagged architecture that’s unlike a lot of other films. To be honest, I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing. But it is an intentional thing.

What happens to Van Buren when he disappears after Erzsébet confronts him?

Jones: Guy always says: “Therapy.”

Pearce: I’ve gone back and forth. The power of him just being reduced to nothing, being gone, nonexistent ... that enabled me to go, “Great. I don’t have to think about this anymore.” Which is pretty lazy of me.

Corbet: My partner, Mona, says that once this character has been dismantled, he is just irrelevant. So it doesn’t matter if he went on a long walk, or if he hung himself, or if he drowned himself, or froze to death out in the forest.

Brody: What happens to Van Buren? I don’t think it’s very good. I think most people come to the same conclusion. The shame, it’s pretty great to be confronted with it. It’s a deeply disruptive moment. They can’t find him, so I interpret it as something terribly final.

Jones: He’s like a sprite. He disappears into thin air.

Pearce: I mean, the obvious thing is some sort of suicide, because this is gonna be just too big for him to bear. But I wouldn’t solidify that. The beauty is that he’s just gone.

Twenty-two years pass and then we see László being feted at the First Architecture Biennale. How do you imagine his life in those intervening decades?

Corbet: I wanted the character to look, visibly, like he’d recently had a stroke and that he’d aged a lot. I was looking at a lot of images of Chet Baker who, at like 57, looked like he was 110.

Brody: It’s interesting witnessing someone you’ve spent all this time with, seeing him much later in life, quite frail, reflecting on his own journey and what he has left behind and the toll it’s taken. For László, there’s a lot of loss. He’s constantly forced to endure. It’s not an easy thing for people to overcome hardship, let alone what he experienced in the concentration camps.

Corbet: There’s a suggestion that some of his projects were realized. There’s a reason we decided to go predominantly with drawings. Even the world’s greatest architects tend to not be particularly prolific. My favorite architect is Peter Zumthor, and he’s been working on the new LACMA for so many years.

Brody: There are opportunities of creative fulfillment, and that is such a deep part of any artistic person’s yearnings. So there is fulfillment in that immersion. But I think as far as a fulfilling personal life that’s brought a great deal of happiness and closure to everything? I don’t know if that has ever come.

Adrien Brody, Kieran Culkin, Colman Domingo, Peter Sarsgaard, Sebastian Stan and Jeremy Strong dive into their films, truth-telling and acting alongside your director.

Corbet: It is a film about legacy, absolutely. But what you’re left with at the end of the film is that László’s legacy is not necessarily the body of work he left behind. His legacy is family and his niece. Through his accomplishments, he has paved the way for her to have some kind of life she might not have had otherwise.

Did he ever build that bowling alley he talked about when he first met Van Buren?

Brody: [Laughs] I don’t think he does. A Brutalist bowling alley. The ball is actually a cube.

Is anyone going to build “The Brutalist” popcorn bucket that I saw mocked up?

Corbet: I think [“Brutalist” co-star] Alessandro Nivola sent that to us. Alessandro wins the internet every day.

Brody: I could help design it. It could be made of paper, like an origami cube. You make it and blow into it, and then it pops open into a sphere, and then you just fold it in and fill it with popcorn. If I wasn’t so busy with my day job, I’d get to it.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.