Man Accused of Hacking Into NASA Computers

- Share via

NEW YORK — Federal agents Wednesday arrested the 20-year-old self-proclaimed leader of a sophisticated group of Internet hackers on charges of illegally breaking into two computers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

Raymond Torricelli, who uses the nickname “rolex,” was taken into custody at his home in New Rochelle, N.Y. Authorities said he had gained access to more than 800 computers, including those at San Jose State University and Georgia Southern University, and possessed 76,000 passwords.

According to the five-count complaint, Torricelli used one of the NASA computers to host an Internet chat room devoted to hacking techniques.

The intrusions at JPL, which occurred in April 1998, were so serious that one of the computers had to be taken offline and the other permanently decommissioned.

But NASA officials said the incidents did not greatly compromise the work of the space agency.

“There was nothing we would warrant as a safety issue,” said Stephen Nesbitt, operations director of the agency’s computer crimes division.

The task of one of the computers that was hacked was satellite design and mission analysis of future spaceflights. The other computer was used as an e-mail and internal Web server.

NASA security agents had been investigating Torricelli for several years and had a court order to obtain his computers for analysis, Nesbitt said.

He said the scrutiny involved informants within the hacker community, as well as people close to Torricelli.

“This case is significant,” Nesbitt said. “The individual had considerable skills.”

According to an affidavit filed in federal court by Mark A. Smith, a NASA supervisory special agent assigned to JPL, he and other agents found data relating to the computer intrusions during a search of Torricelli’s bedroom on Nov. 18, 1998.

The search team reportedly discovered intercepted electronic communication from San Jose State, Georgia Southern and other colleges. They also found unauthorized computer passwords and credit card numbers, as well as programs capable of intercepting computer network traffic.

When the agents told Torricelli he was not under arrest at that time, he agreed to be interviewed, according to the court papers.

During the questioning, Torricelli said that he was head of a group called “#conflict,” one of whose purposes was to engage in computer hacking. Other members, he said, included people who used the nicknames “blood,” “endless,” “zerox” and “bomb.”

Beyond their nicknames, these people were not further identified by federal officials, who said the investigation was continuing.

Torricelli reportedly told the agents that he got the credit card numbers from “blood,” which he then used to purchase phone service. He also said that he obtained user names and passwords from people in chat rooms, which allowed him free Internet access and enabled him to gain unauthorized entry into computers.

The court papers alleged that data from Torricelli’s personal computer revealed some of the chat room discussions--involving stealing credit card numbers and using them for purchases and possibly logging a large number of votes onto MTV’s Web site to rig the annual MTV Movie Awards.

The affidavit alleged that the group illegally installed a network “sniffer” program on one of the NASA computers, allowing members to intercept the names of users and passwords.

Investigators also reportedly found on Torricelli’s computer more than 100 stolen credit card numbers. The complaint said Visa, American Express, MasterCard and Discover reported that the real owners of the cards had complained of fraud totaling more than $10,000.

The JPL attack is the latest in a never-ending barrage of computer strikes aimed at government networks.

“We’re aware of six or seven [government networks] broken into every day,” said John Vranesevich, founder of the Pennsylvania-based computer security firm AntiOnline. “Many government systems are hacked into for months before people operating the systems notice.”

The hackers rarely gain access to sensitive information, which is typically stored on systems that can’t be reached from the public Internet, Vranesevich said. Often the greatest danger, he said, is that hackers will stumble into critical data that have been moved to unprotected systems by careless employees.

Some of the best-known attacks in recent years have been designed more to embarrass government agencies than to steal data from them. Last year, Web sites operated by the White House and the Senate were defaced by hackers from a group called GlobalHell, who were protesting the arrest of one of their comrades.

Recently, NASA acknowledged that a hacker had interfered with the transmission of astronaut medical data in 1997 but said that it affected only low-security ground communication and that the problem was quickly corrected by backup systems.

In 1998, members of another group, called Noid, broke into military computers and, before the systems were patched, were able to download software that controls the positioning of satellites.

Vranesevich said that Torricelli’s varied targets and the 76,000 passwords indicated that he was more interested in stockpiling hacking trophies than undermining a specific system. “There was probably no one particular thing he was looking for. He was just showing off.”

Mary Jo White, the U.S. attorney for the southern district of New York, said that hackers who gain access to restricted government computers and damage them are not harmless pranksters.

“They are criminals and will be dealt with vigorously,” she stressed.

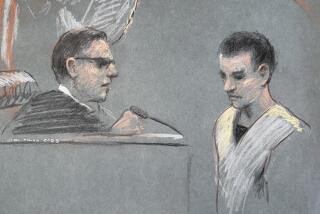

U.S. Magistrate Judge Mark D. Fox released Torricelli, who appeared in federal court in White Plains, N.Y., on a $50,000 personal recognizance bond.

If found guilty, he faces up to 10 years in prison and a $250,000 fine on charges of credit card fraud and password possession; five years in prison and a $25,000 fine on a charge of password interception; and one year in prison and a $100,000 fine on each of two charges involving unauthorized access to the NASA computers.

*

Goldman reported from New York and McFarling from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Greg Miller in Los Angeles also contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.